Cattleya schilleriana 'JEM' AM/AOS Exhib: J.E.M. Orchids; photo © Greg Allikas

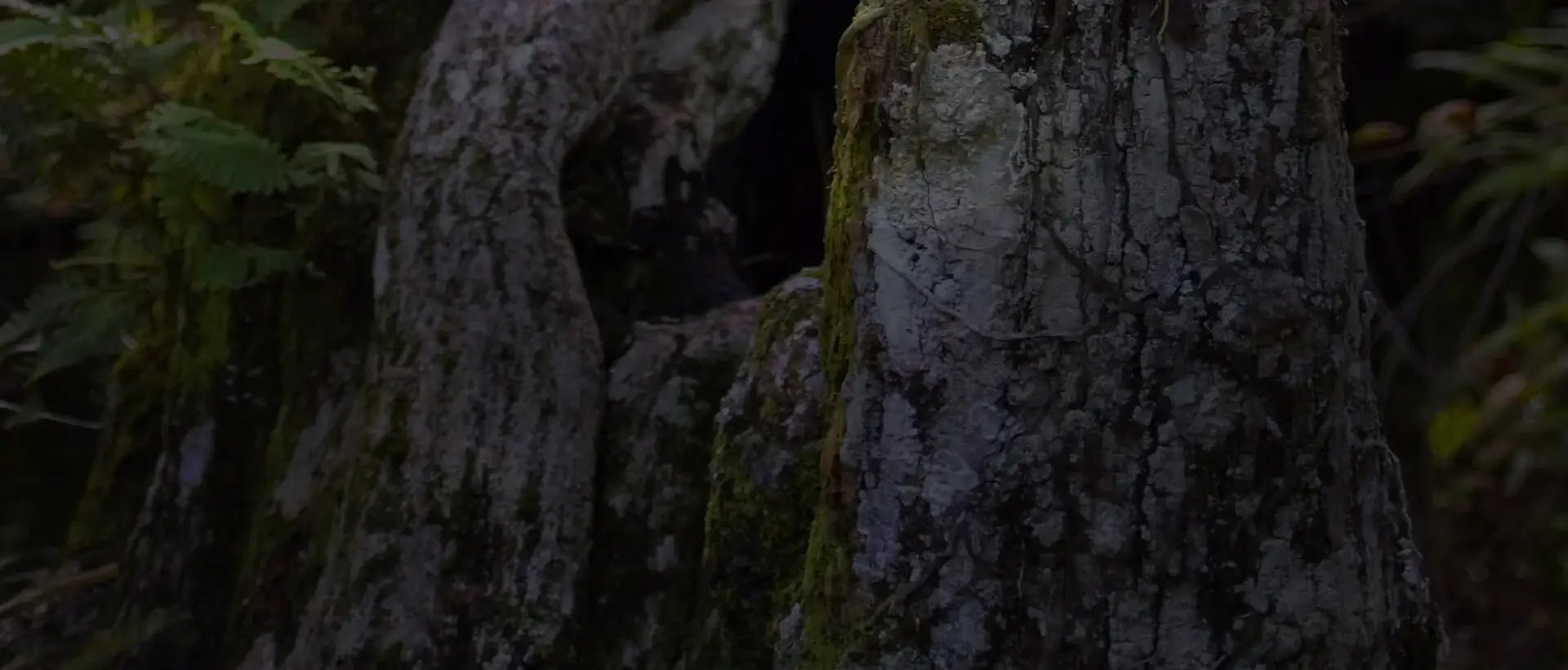

Cattleya schilleriana is one of the most under-appreciated gems of the Cattleya Alliance, if not the entire orchid family. It is a small-growing member of the bifoliate tribe of cattleyas, which have two leaves on each pseudobulb. Mature plants of C. schilleriana are approximately 10 inches tall, individual flowers are about 4 inches across and there may be four to six flowers per inflorescence on a well-grown plant.

The flowers are deliciously fragrant, waxy and have a high sheen. Petals and sepals, in varying shades of tan, brown and mahogany are overlaid with much more intensely colored spots. Perhaps the most striking feature of all is the lip, which is white with rich magenta stria-tions. On good specimens, it is perfectly flat and 2 inches across. This brilliant rich lip garners attention, even from across the showroom floor, and invites viewers to come and investigate. Upon closer inspection, you notice the wonderful fragrance, glossy sheen, exotic spotting and abundance of flowers.

I like to describe C. schilleriana to my friends as a new and improved Cattleya aclandiae. Cattleya schilleriana has dramatically more flowers per inflorescence than does C. aclandiae (four to five versus one to two) and the individual flowers are somewhat larger (4 inches versus 3 inches). Their fragrance is headier and more penetrating and the striations of the lip come out and grab you in a way that the solid-colored lip of C. aclandiae does not. The flowers on C. schilleriana last for approximately three to four weeks, which is about twice as long as for those of C. aclandiae. Cattleya schilleriana is much easier to grow than C. aclandiae, which must be grown on a mount and has a rightfully deserved reputation as being finicky. Cattleya schilleriana grows well in a pot and is no more difficult to cultivate than the average bifoliate cattleya.

Although initially discovered in 1857, plants of this species were uncommon in cultivation prior to the mid 1970s. One reason for this may be their extreme rarity in nature. They are apparently found only along two or three streams in a small area of Brazil. Beginning in the 1970s, a number of plants were imported from Brazil. Although it is still not common in collections, a number of growers now sell seedlings grown from these original imports.

Cattleya schilleriana 'Tejas', HCC/AOS Exhib: Ken Avant; photo ©James Harris

CULTURE FOR THIS CATTLEYA

New growths emerge in early spring and blooming occurs after the growths mature in April through June. Generally, new roots do not emerge until immediately after flowering. In cultivation, it is not uncommon for plants to send up another growth or two during the summer. Infrequently, these summer growths will bloom over summer and autumn as they mature, but it is more typical that these growths will never flower. The plant appears to go into a dormant stage during autumn and early winter until new growths appear again in late winter or early spring.

Temperature

Cattleya schilleriana basically grows well under conditions provided for cattleyas. The temperature range in its native habitat is apparently a little on the cool side of standard cattleya conditions. Summer temperatures never climb above the low 80s and winter temperatures fall as low as 46 F. Therefore, it might be advisable to look for a slightly cooler than average spot in the cattleya house, particularly during winter. Cattleya schilleriana grows well for me in a greenhouse where winter temperatures drop to 60º F at night. For many years I successfully grew equally good specimens under lights in my home, where evening temperatures were higher and there was little temperature drop in the evenings.

Watering

In its native habitat, there are four dry months during the summer when there is no rain, corresponding to June through September in the Northern Hemisphere. All of autumn and winter is somewhat rainy. Then the true rainy season begins in the spring. The plants begin their new growths and flower during the rainy season. Although there is no rain during the summer, the dews are extremely heavy, so that there is no extremely dry season for these plants in nature when they completely dry out.

Most successful growers of this species seem to grow their plants a little on the dry side during the autumn and winter. When plants are actively growing in spring and summer, they are given more water.

My experience has been that plants are larger and more robust when grown in containers, rather than on mounts. In order to allow them to dry out properly between waterings, pot in a porous medium such as plain medium fir bark. Do not attempt to grow this species in peat-based mixes. It may be that using a clay pot is also a good idea, but the most important thing is to use a porous mix such as plain medium-grade fir bark. For plants in 5- and 6-inch pots, I use clay and plastic interchangeably. However, for mature specimens in larger containers, I always use clay.

Cattleya schilleriana 'Julia Valeria', AM/AOS Exhib: Alejandro Rodriguez Cheung photo © Jorge E. Cespedes

The only minor point of controversy regarding watering practices that I am aware of concerns how dry the plants should be grown over the summer months after blooming ceases. In their natural habitat, there is no rain for a three- or four-month period. However, there are heavy dews. My practice has been to water them like all of my other orchids during this period and to rely on the porous mix to keep them a little drier. This usually means watering 5-inch pots two or three times per week and 8-inch pots twice per week. In winter, I maintain about the same level of wetness by halving the amount of watering. Therefore, I do not try to create an extremely dry period in summer. Under this regime about half of my plants send up summer growths and the other half do not.

It is possible that there may be some advantage to trying to make the summers drier. One of the best growers of C. schilleriana that I know insists that this species must be given a distinct rest during summer after the blooming is over. He claims that the nonblooming summer growths observed by many growers only occur if the plants are not dried out properly, and that plants that produce these nonblooming summer growths do not bloom as well the following year. This type of regime seems extreme to me, and I settle for growing them a little on the dry side. There is room here for some controlled experimentation.

Repotting

As for all bifoliate cattleyas, it is extremely important to repot these plants only when active roots are just beginning to appear. This would usually mean that plants would be repotted in early summer immediately after flowering. Plants of this species often suffer a setback for a year or so after being repotted. Therefore, it is best to delay repotting as long as possible. Plants of C. schilleriana are relatively compact so it is generally possible to keep plants in the same container for three or more years. Because they are grown in a fairly porous medium and kept on the dry side, I have never experienced problems with decomposing bark.

Light

I grow all of my cattleyas in light intensities toward the high end of what is normally recommended for cattleyas and my plants of C. schilleriana seem to do fine under these conditions. The leaves and stems become heavily stained with dark anthocyanin pigments. I have observed that the coerulea forms of C. schilleriana are more susceptible to burning, and I generally grow them in slightly more shaded conditions. This is possibly because the coerulea forms all seem to lack noticeable anthocyanin staining in their vegetative parts. This pigmentation helps protect the leaves from burning in the non-coerulea forms.

Under-lights Culture

Cattleya schilleriana is an ideal species for growing under lights due to its short stature. Under high light, the leaves generally are held relatively horizontal with respect to the ground, so that the entire leaf surface can be exposed to equally strong light under lights. Position the plants so their leaves are within a few inches of the tubes.

William P. Rogerson — reprinted from ORCHIDS (abridged), September 1997