STEPHEN R. BATCHELOR

A revolution in Phalaenopsis hybridizing began in the 1960's. Phalaenopsis species previously little-used in breeding caught the attention of hybridizers. The influence of these lesser-known species began to be seen in hybrids whose flowers were unusually colored and patterned. This trend has continued, at a rapid rate, until today pink or white hybrids — without these "newer" species in their ancestry — are in a definite minority among Phalaenopsis hybrid registered and awarded. Yet today's phalaenopsis are not just more variable in color than hybrids of twenty years ago. They also vary radically in flower size and thickness (substance), and in the way they present their flowers. This, too, can be attributed to the introduction of a wider range of species into Phalaenopsis hybridizing.

Figure 1 Phalaenopsis bellina 'Shamrock', HCC/AOS grown by Robert & Nancy Gordon

PHALAENOPSIS BELLINA AND ITS HYBRIDS

Phalaenopsis hybridizers discovered another source of intense pink (besides Phalaenopsis pulcherrima) in the flowers of Phalaenopsis bellina [editor’s note: Until fairly recently this species was considered to be a varietal form of a Phal. violacea. When originally published this article called it such. Phalaenopsis bellina is from Borneo, distinctly different from the Malaysia to Sumatran distribution of Phal. violacea.], from the island of Borneo. The flowering habit of this species differs drastically from that of the white or pink Phalaenopsisspecies discussed in the previous article for this series. By way of illustration, the cultivar of Phalaenopsis bellina pictured in figure 1 has three inflorescences averaging 15 cm (6 inches) long. These will continue to lengthen as they produce successive flowers from their terminal growing points. The flowers illustrated are heavily colored in pink only on the column, lip and inner portions of the lateral sepals. They measured 4 cm (1.5 inches) horizontally and 6.5 cm (2.5 inches) vertically.

Figure 2 Phalaenopsis Hugo Freed (Ella Freed x Mad Lips) grown by Ralph and Chieko Collins. Photograph copyright Stephen R. Batchelor.

In recent times, hybridizers have crossed Phalaenopsis bellina (under the name Phal. violacea) with many other Phalaenopsis species as well as complex hybrids. Today, hundreds of intensely colored hybrids exist which have some degree of Phalaenopsis bellina in their backgrounds. Readers and writers alike should be wary of generalizations, particularly when it comes to orchid hybridizing; nevertheless, the first three illustrations in this article give an indication of the kind of influence Phalaenopsis bellina has on complex, modern hybrids. When Phalaenopsis bellina (under the name violacea) was crossed with the complex, pink-striped Phalaenopsis Hugo Freed (Fig. 2), an undetermined number of seedlings resulted of the unregistered hybrid, Phalaenopsis (Hugo Freed x bellina), one of which is pictured here (FIGURE 3). A comparison of Figures 2 and 3 will help us characterize the influence of the species.

Figure 3 Phalaenopsis (Hugo Freed x bellina) grown by Ralph and Chieko Collins. Photograph copyright Stephen R. Batchelor.

Most evident is the intensification of color in the flowers of Phal. (Hugo Freed x bellina). This can be attributed to Phalaenopsis bellina. Not so obvious, however, within the confines of these photographs, is the enhancement of the substance (thickness) of the flowers in figure, 3. On the other hand, going from Figure 2 to figure 3, the flower size and inflorescence length have been reduced, a result likewise attributable to Phalaenopsis bellina. While the flowers Phal. Hugo Freed in Figure2 were 10 cm (4 inches) across, those of Phal. (Hugo Freed X bellina) in figure 3 measured 6.5 cm (2.5 inches) across. The inflorescence in figure 2, 70 cm (27 inches) long and bearing nine flowers, is considerably longer than the 26-cm (10-inch) inflorescence of four flowers in Figure 3. The question now remains whether the two flowerings represented in these photographs reflect the full potential of the two hybrids involved. Though it is likely that older, larger plants in both cases will produce longer inflorescences carrying greater numbers of flowers, the difference in these characteristics of flowering between the two hybrids will probably continue. This reduction in flower size, floriferousness and inflorescence length from more conventional pink Phalaenopsis and Doritaenopsis hybrids where Phalaenopsis schilleriana, Phalaenopsis sanderiana or Phalaenopsis pulcherrima are the source of color can be seen in a broad examination of contemporary hybrids heavily influenced by Phalaenopsis bellina (Freed, 1980a). [editor’s note: While written in 1982, the characteristics of reduced flower count and inflorescence length have held. However these tendencies prove to be offset in larger plants by the tendency of inflorescences to branch – a characteristic also inherited from Phal. bellina and violacea. Each branchlet of the mature inflorescence carries flowers often dramatically increasing the number of flowers actually carried on a plant.]

Figure 4 Phalaenopsis lueddemanniana var. ochracea'Stones River', HCC/AOS grown by Stones River Orchids and photographed by Edwin S. Boyett

YELLOW PHALAENOPSIS SPECIES AND THEIR HYBRIDS

With the introduction of Phalaenopsis mannii, Phalaenopsis lueddemanniana and Phalaenopsis amboinensis into contemporary breeding, the yellow phalaenopsis appeared, and evolved. Phalaenopsis lueddemanniana quickly gained predominance in hybrid registrations during the sixties (Vaughn, 1974, page 144), and accordingly has its influence felt in a large proportion of yellow, as well as pink and pink-striped, modern hybrids (Freed, 1981).[editor’s note: Since the publication of this article, it has become apparent that many of the plants labeled as Phal. lueddemanniana used in early breeding were in fact probably fasciata or other yellow base color flower. Hybrids actually made with Phal. lueddemanniana are most often white base color flowers.]

Phalaenopsis lueddemanniana has been a troublesome species to define — for the taxonomist, hybrid registration authority, hybridizer and hobbyist alike! For many years orchidists have been growing plants called Phal. lueddemanniana var. ochracea, Phal. lueddemanniana var. hieroglyphica, Phal. lueddemanniana var. pulchra and other varieties of the species. Dr. Herman Sweet, noted orchid taxonomist, in his revision of the genus (Sweet, 1980) contends that a majority of these varieties are in fact species, and he designates them as such: Phalaenopsis hieroglyphica and Phalaenopsis pulchra, among others. Dr. Sweet continued to accept as valid, however, Phalaenopsis lueddemanniana var. ochracea, pointing out, though, that many plants in cultivation with this name are mislabeled, being in fact cultivars of Phalaenopsis fasciata, a very similar-looking species.

The International Registration Authority of the Royal Horticultural Society of England, which registers and publishes all orchid hybrids, did not accept this revision for practical reasons: "The second point concerns such species as Phalaenopsis lueddemanniana and its many varieties, several of which Dr. Sweet has evaluated to species level. Although we may accept this botanically, to accept it horticultural would cause very considerable confusion in hybrid registration because it would be necessary to identify which variety had been used for past crosses involving P. lueddemanniana." (Hunt, 1971, page 24) As a result, no hybrids have been registered with these varieties (or related species, depending on your allegiance!) of Phalaenopsis lueddemanniana. [editor’s note: Present-day hybrid registration does recognize and register hybrids of Phal. pulchra and hieroglyphica as distinct from those of Phal. lueddemanniana. In nature an ambiguous array of flowers has evolved which are, superficially at least, very similar, but which vary widely in color and patterning. Flowers of plants (usually) called Phal. lueddemanniana var. hieroglyphica typically have pale yellow background color with interesting clusters of brownish dots across the sepals and petals. In contrast, flowers of plants called Phal. lueddemanniana var. pulchraare often a vivid pink. The flowers of Phal. lueddemanniana var. ochracea are to some degree yellow, with an overlay of reddish-brown patterning (figure 4).

Phalaenopsis lueddemanniana var. ochracea 'Stones River', hcc/aos (figure 4) — disregarding whether any one clone of Phal. lueddemanniana can be representative of the color and patterning of the species as a whole — illustrates the flower characteristics and flowering habit of the species. This plant, when awarded, displayed 25 flowers and 4 buds on 11 inflorescences. The flowers of heavy substance averaged 6.7 cm (2.5 inches) in natural spread. This particular clone resulted from a selfing of Phalaenopsis lueddemanniana var. ochracea 'J & L', am/aos (awarded in 1965). But was this plant correctly labeled, or was it, in fact, a cultivar of Phalaenopsis fasciata?

Hugo Freed, one of the most successful of Phalaenopsis hybridizers, in an article on Phalaenopsis fasciata and its hybrids, relates the following story: "For example, Phalaenopsis Inspiration (Juanita x lueddemanniana) was registered by Santa Cruz Orchids in 1961. Several years later I was informed by the breeder that a flower of this Phalaenopsis lueddemanniana (var. ochracea) was sent to Dr. Herman Sweet for identification and was identified as Phalaenopsis fasciata. The registration was never corrected . . ." (Freed, 1980b, page 1099). In that same article (page 1100) two clones of Phalaenopsis Inspiration — one yellow and one pink are illustrated. We can only assume that one clone had a yellow-flowered species parent, the other a pink-flowered one. Whether they really should have the same hybrid name (and parentage) could certainly be debated!

Figure 5 Phalaenopsis Golden Sands 'Zuma', HCC/AOS grown by Arthur Freed Orchids and photographed by Richard Clark

Putting aside this unresolvable issue, many yellow hybrids have been registered with Phalaenopsis lueddemanniana as a parent. Phalaenopsis Golden Sands, registered in 1964, is one of the most successful of the earlier yellow hybrids, receiving over a dozen American Orchid Society flower-quality awards in the late 1960's and early seventies. This hybrid resulted when Phal. lueddemanniana (a yellow cultivar) was crossed with a complex, white Phalaenopsishybrid. Many of the early yellow hybrids were created from a similar kind of cross. Phalaenopsis Golden Sands 'Zuma', hcc/aos (figure 5) exhibited 6 flowers and 10 buds on one inflorescence when awarded. The flowers measured 3.75 inches (9.5 cm) across and were "cream-yellow" spotted with "rose-pink", according to the award description. Looking at these flowers, and comparing them with those in figure 4, it would seem that the complex hybrid parent has dominated over the species parent in terms of flower size and form, and inflorescence length. Hugo Freed points out, in his discussion of PhalaenopsisGolden Sands that most clones tend to fade soon after the flowers open. Phalaenopsis Golden Sands 'Canary', fcc/aos, however, does not (Freed, 1980b, page 1104).

Figure 6 Phalaenopsis amboinensis 'Medford Honey', AM/AOS grown by Breckinridge Orchids

Much subsequent hybridizing of yellow phalaenopsis in the seventies and eigthies has focused on intensifying the color and patterning of the flowers.Phalaenopsis amboinensishas been heavily used in breeding in recent years for this purpose. In the latest addendum to theSander's List of Orchid Hybrids, 64 new hybrids are listed with this species as a parent, 58 forPhalaenopsis lueddemanniana(Royal Horticultural Society, 1981).Phalaenopsis amboinensiscultivars do vary in the amount of yellow present on the flowers, and it is probably the yellowest cultivars with the boldest patterning which have been most frequently used in breeding (Freed, 1980c). The clone ofPhalaenopsis amboinensisin figure 6 is fairly representative of the yellower cultivars of this species. These flowers, of almost leathery substance, measured 5.0 cm (2 inches) wide, and are not as full (broad in their sepals and petals) as some awarded cultivars have been. The inflorescences of this species have been known to reach 45 cm (1.5 feet) in length, though they are "commonly few-flowered" (Sweet, 1980). From the ends of these lax inflorescences flowers are produced in succession. They open, age and fall to be replaced by others farther down the stem. (Note the flowerless bracts farther up the inflorescence in figure 6, where flowers appeared earlier.) In this way the inflorescence continues to lengthen, while having a few flowers open at a time.

Figure 7 Phalaenopsis Solar Flare 'Gordon', AM/AOS grown by Wassie Orchids and photographed by Charles Marden Fitch

Phalaenopsis Solar Flare, registered in 1979, is just one of the many recent hybrids which are heavily influenced by Phalaenopsis amboinensis, as well as Phalaenopsis lueddemanniana and Phalaenopsis fasciata.This particular hybrid is a cross of Phalaenopsis Golden Sands (Juanita x lueddemanniana), discussed earlier, and Phalaenopsis Golden Pride (fasciata x amboinensis). Six awarded clones of Phalaenopsis Solar Flare appear in the awards quarterly for 1981, with an average score of 80 points (an Award of Merit on the American Orchid Society scale for flower quality). These six awarded plants averaged 3-4 flowers on an inflorescence, though one award description, for a plant with two flowers, mentioned that greater floriferousness could be expected, as the plant was young at the time of the award. The flowers for the six clones averaged 5.7 cm (2.25 inches) in natural spread. In all six instances, the flowers were described as being intensely yellow and patterned, in addition to having exceptional substance.

Figure 8 Phalaenopsis cornu-cervi 'Bryon', HCC/AOS grown by Bryon K. Rinke and photographed by Karl Siegler

Phalaenopsis Solar Flare 'Gordon' (figure 7) recently received an AM/AOS of 80 points. In the award description for this clone, it was noted that the "Petals and sepals [were] broad, flat and well-overlapped for the cross. Judges commented on the crowded presentation of the flowers at the end of the spike as distracting from the overall esthetics of the plant. The flower natural spread of flower was 6.0-cm [2.5 inches]". Since the inflorescences pictured in all likelihood would have assumed a semi-pendent position over the leaves, much like the species making up this hybrid, if they had gone unstaked, some debate occurred between the judges as to whether or not the plant should have been presented in this fashion.

Perhaps controversy and phalaenopsis go hand-in-hand! Several questions are raised by hybrids such as the one just discussed; questions which need to be addressed, not just by orchid judges, but by the hobbyist, who has to choose which phalaenopsis lo include in his or her collection. How much are we willing to compromise in order to have flowers of unusual color?

To determine whether the orchid-judging community has altered its standards in order to award bright yellow phalaenopsis, we need only imagine the (lowers in figure 7 as being white. Would a white phalaenopsis with three 2.5 inch flowers clustered at the end of a long, weak inflorescence have been awarded? Clearly it would not. But is it fair to make this comparison when the influencing species in each case are so radically dissimilar? Not entirely, and yet we have to recognize this difference. We do indeed alter our expectations for "novelty" phalaenopsis from what we expect in more conventional, white or pink hybrids. It seems that we are willing" to accept a reduction in flower size and fullness for intense and unusual colors and patterns. But are we willing to accept a significant reduction in floriferousness as well? Is more intense color, and thicker flowers, sufficient compensation for all this? The answer to this question will naturally vary from hobbyist to hobbyist. Not just the esthetics, but the growing situation of the individual has to be considered. Would someone who grows under conventional fluorescent lights want a doritaenopsis, for example, which throws upright spikes many feet tall? Such a trait would cause problems. What could be done with the inflorescence once (or if!) it cleared the lights:1 under the circumstances it would be difficult to get such an inflorescence to develop properly. Phalaenopsis with shorter, more arching inflorescences might be just what is called for. Yet, could not such hybrids, at the same time, provide an abundance of flowers? This discussion ofPhalaenopsishybridizing is limited, both by the few hybrids and species considered, and by the fact that the writer does not himself breed phalaenopsis! Hybridizers do not view any onePhalaenopsishybrid as an end unto itself, but rather, I imagine, as one intersection in an evolving network of hybrids, the history of which is comparatively young, and full of deterrents, such as sterility, which the non-hybridizer isn't even aware of. Can we expect "perfection" (in our own terms, of course!) in Phalaenopsis hybrids so soon?

THE MERITS OR PHALAENOPSIS SPECIES

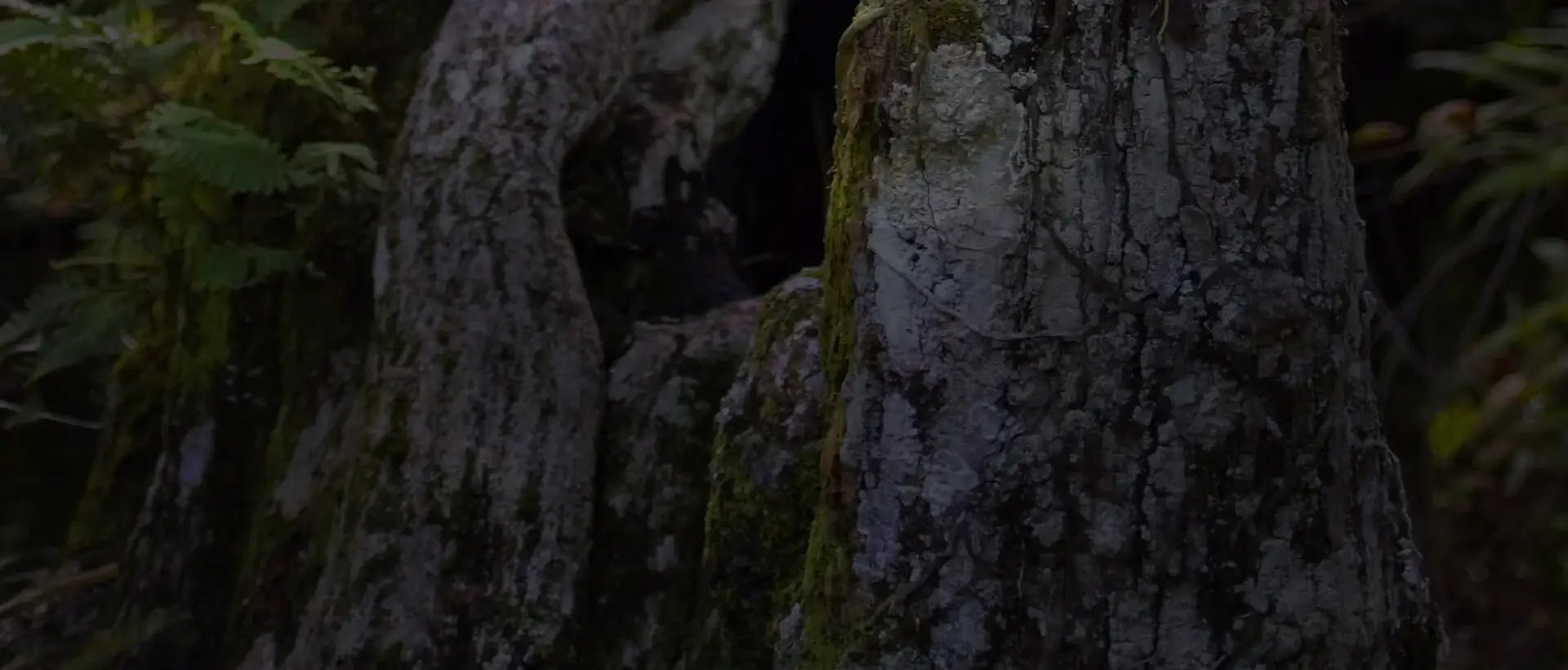

There are those among us who disregard all this "nonsense" about hybrids and are content with a collection comprised solely of orchid species. Are they "extremists" to be dismissed outright? We sometimes forget that 25,000 species created by nature alone could be considered enough for all but the most spoiled of horticulturists! The genus Phalaenopsis, as mentioned in the previous article, offers 40 species (give or take!) and a tantalizing variety of flowers and flowering habits. To give "equal time" to those species which do not have large, rounded flowers on more upright inflorescences, included here are pictures of two species which have compensations other than ostentatious flower display! The open flowers of Phalaenopsis cornu-cervi in figure 8, 5 cm (2 inches) long and 4 cm (l.5 inches) across, could hardly be characterized as "dinner plates" as some white Phalaenopsis hybrids have. Nor could a display of a flowering specimen of this species in all honesty be called "stunning". Instead, Phalaenopsis cornu-cervi has branched, pendent inflorescences which are themselves of interest, though they have but few flowers at any one time. They are flattened, with the bracts of past flowers, since dead and gone, alternating down either side. The inflorescences in figure 8 measure 45 cm (1.5 feet) long, and are by no means stopping there, but will continue to lengthen as new flowers are produced. They have flowered, and will continue to flower, for years!

Figure 9 Phalaenopsis mariae 'Liberty Hill', CCM/AOS grown by Ralph and Chieko Collins and photographed by Charles Marden Fitch

Phalaenopsis mariae rivals Phalaenopsis cornu-cervi in this regard. At the time a Certificate of Cultural Merit was awarded Ralph and Chieko Collins for their Phalaenopsis mariae 'Liberty Hill' in June, 1978, the plant had 145 5-cm (2-inch) flowers on 11 pendent inflorescences partially obscured by its broad leaves (figure 9). Four and a-half years later, these same inflorescences are still in flower, only now they are 45 cm (1.5 feet) in length with the flowers in full-view far below the plant. Next month begins a discussion of the culture of this wonderful genus of species and hybrids. — January 1983

Bibliography

Freed, Hugo. 1980a. An Up-date on Breeding with the Borneo-type Phalaenopsis violacea. Amer. Orchid Soc. Bull. 49(8): 843.

Freed, Hugo. 1980b. The Fabulous Phalaenopsis fasciata. Amer. Orchid Soc. Bull. 49(10): 1099. Freed, Hugo. 1980c. Phalaenopsis amboinensis. Amer. Orchid Soc. Bull. 49(5): 468.

Freed, Hugo. 1981. The Versatile Phalaenopsis lueddemanniana — Parts 1 and 2. Amer. Orchid Soc. Bull. 50: 1077, 1325.

Hunt, Peter. 1971. Registration of Phalaenopsis Hybrids. The Orchid Review. 79(1): 23.

The Royal Horticultural Society. 1981. Sander's List of Orchid Hybrids, 5 Year Addendum, 1976-1980. London, England.

Sweet, Herman R... Ph.D. 1980. The Genus Phalaenopsis. The Orchid Digest, Inc.

Vaughn, Lewis and Varina. 1974. An Account of Moth Orchids: The Years of Change. Amer. Orchid Soc. Bull. 43(2): 140.

Woodward, George P., Jr. 1971. Phalaenopsis Species CAN Be Fun!Amer. Orchid Soc. Bull. 40(9): 772.