SOME PEOPLE ONLY buy orchids in bloom so they can choose which orchid flower they like the best. These plants are usually more expensive because they are mature enough to flower and are often sold in a larger pot. If I see a drop-dead gorgeous flower, I may throw my Scottish heritage to the winds and buy the flowering plant, but more often than not, I can be found at the seedling sales tables, where small plants in 2- to 3-inch (5–7.5 cm) pots are being offered.

[1] How do you decide which or how many seedlings to bring home?

Buying seedling plants in smaller pots is a more cost-effective way of expanding your collection. Of course, you must grow it into a mature size before it will flower well for you, and this is contrary to the instant gratification we often seek. But there is something special about growing a small plant into a large plant and seeing the buds form and the flowers open for the first time.

Some people are overwhelmed by trays of seedlings. They are unsure which variety to buy, or which plant they should select. Some reflexively buy one of each seedling offered. Perhaps a more rewarding approach is to evaluate how variable the seedlings may be and buy multiples of the ones that will likely show a spectrum of flower colors, sizes and shapes so you can select the best ones to keep in your collection.

The first thing to determine when you are shopping is whether the plant is a mericlone, in which case all the seedlings in the tray are theoretically genetically identical. Mericloning is a tissue culture technique used to mass-produce orchids (and other plants). Meristematic (actively growing) tissues, such as the shoot tips, buds, etc., are cut from a plant and grown using fairly elaborate chemical and mechanical procedures under clean and sterile conditions producing potentially thousands of plants, all identical to the original. If you see a tray of mericlones, you are looking for a healthy, vigorously growing seedling that you can bring home, expecting it to bloom exactly like that sample plant or picture. You only need to buy one.

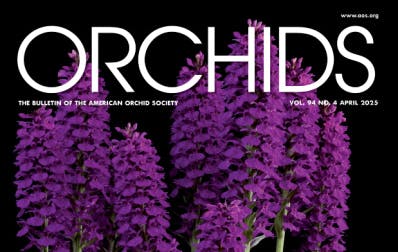

[2–4] You can see the open hairy lip from Ctsm. fimbriatum [2] and the wide sepals from Ctsm. saccatum [3] in the primary hybrid Ctsm. Dragon’s Teeth ‘Sunset Valley Orchids’ AM/AOS [4].

In nature, populations of orchids readily interbreed, thanks to their pollinators, producing variations in the color, shape, size, etc. in the next generation of orchids. This is all too random for the dedicated species breeder who would like nothing better than to improve on Mother Nature. If you see a tray of species seedlings propagated by seed, check whether it is a selfing, a sibbing or an outcross to give you some idea of how much variation you might expect in the offspring. If it is a sib cross, where two plants from the same seed capsule are interbred, or an outcross, where two cultivars of the species are bred together, the hybridizer was likely line breeding. Line breeding is used to attempt to improve the shape, form, size, color, etc. of the hybrid by using two select forms of the species to produce even better offspring. You would expect a relatively uniform group of progeny. There will undoubtedly be one that has a slightly bigger flower, better shape or more color. You will once again look for a vigorous growth habit, perhaps wider leaves or thicker substance. You might just select one of these from the tray, or if you really like the species, maybe a few to bloom out and select the one you like best as the keeper.

If it is a selfing, where the pollen from a plant is placed on its own stigma to form seeds, either the hybridizer only had one plant to propagate, or the hybridizer is trying to tease out some recessive traits from the parent plant. By recombining the parental genes, you would expect more variation in the offspring than with a sibbing, with a few perhaps that exhibit some recessive trait such as an unusual color. You might select one from the tray, although you might be tempted to buy multiples to see if you can get lucky and find a rare color form.

With hybrids, the degree of variation depends on the parents. Primary hybrids are the product of two interbred species so the offspring get half the genes from the capsule parent and half from the pollen parent. The hybrid seedlings are midway between the parents, with only a little variation such as what you see in your brothers and sisters. Another benefit is they often exhibit hybrid vigor, where the primary hybrid is easier to grow than either of its parents. Species often have evolved to thrive in a unique ecological niche, so the meshing of genes from two species frequently results in plants that can tolerate a broader range of climatic conditions.

Catasetum Orchidglade is a primary hybrid of expansum (left) and pileatum. It was backcrossed to expansum to produce Ctsm. Susan Fuchs (right). Left: Ctsm. expansum ‘Linda’; center: Ctsm. Orchidglade ‘Davie Ranches’ AM/AOS; right: Ctsm. Susan Fuchs ‘Burgundy Chips’ FCC/ AOS. Photographs by Fred Clarke.

If one of the primary hybrid’s parents is a tetraploid (usually denoted as 4n on the plant tag), it has twice the number of chromosomes as the diploid parent and will have greater influence on the offspring, with the offspring looking more like the tetraploid parent.

If the primary hybrid is then crossed with another cultivar of the same primary hybrid in a sib or outcross, there will be a lot more variation in the offspring compared to a hybrid between the two species. The genes will sort differently so the progeny will be more variable, looking more like the capsule or the pollen parent or anywhere in between. As Courtney Hackney explains in American Cattleyas:

The only hybrids that always contain a specific proportion of chromosomes from one parent are primary hybrids, a cross between two species. They inherit one set from each parent. If two siblings of a primary cross are used to make a hybrid, individual seedlings may contain any combination of chromosomes that originated with either grandparent species from 100% to 0% although the probability for such an extreme event is rare.

If you decide to buy more than one plant, you might select your seedlings based on the plant morphology, selecting one having the widest leaves, one having the tallest growth habit or one having lots of red pigment showing in the leaves if looking for color or no pigment if looking for an alba.

When primary hybrids are crossed with different species or hybrids, the progeny is known as a complex hybrid. The goal of most hybridizing is to blend the desirable characteristics of each parent to produce a plant or flower that is an improvement over either parent. The hybridizer might be trying to combine the flower size from one parent with the flower color from the other parent. After several generations of breeding and crossbreeding, it can be difficult to see the contributions from the various species involved in the hybrid.

The more complex the hybrid, the more variation you expect in the progeny. When you find a seedling you think might be interesting, ask the vendor how variable he expects the offspring to be. You might consider buying multiples of a seedling that strikes your fancy so you can enjoy the variety imparted by the different genes inherited from the parents.

References

Batchelor, S. 1982. Beginner Series Orchid Culture 11, Nomenclature, and Seedlings “Versus” Mericlones. American Orchid Society Bulletin 51(1):7–10.

Hackney, C.T. 2004. American Cattleyas: Species and Outstanding Clones That Define American Hybridizing. Wilmington, NC: Courtney T. Hackney, p 123–127.

Slump, K. 2006. Hybrid Hype, Orchids. 72(4):498–500.

Acknowledgment

Thanks to Dr. Courtney Hackney for his critical review and editing of this article, he never fails to improve on the original.

— Sue Bottom started growing orchids in Houston in the mid–1990s after her husband Terry built her first greenhouse. They settled into St. Augustine, Florida, Sue with her orchids and Terry with his camera and are active in the St. Augustine Orchid Society, maintaining the Society’s website and publishing its monthly newsletter. Sue is also a member of the AOS Editorial Board (email: sbottom15@gmail.com).