LIKE MY EARLIER Water Your Orchids article (January 2014), this topic may seem to be awfully basic and pretty obvious, but I believe that if we understand some of the “why” behind the “what” or “how to” information we learn, it puts us way ahead in our efforts to become reliable caregivers to our orchids. The question of “when” to repot is another that arises frequently, and we will address that, too. First, a little bit about our favorite plants.

Many of you may have heard that “healthy roots means a healthy orchid” — again pretty obvious, but do you know why that is? Terrestrial plants, with their roots buried in the soil, do the vast majority of their gas exchange processes through openings (stomata) in their leaves. Orchids, on the other hand, have adapted to having far fewer leaf stomata as an apparent evolutionary strategy to minimize water loss. Those that remain are concentrated on the bottom of the leaves, and in some cases, the plants have developed a thick, waxy “cuticle” layer, all of which shifts much of the gas exchange burden to the root system. If we stifle that, we cause stress and even death to the root cells.

Let me add a bit more about those root cells. As roots grow, they “tailor” themselves to the environment into which they are growing so that they can function optimally to support the plant, and once those cells have grown, they cannot change. We can see the implications of that with the following scenario:

A plant is potted up in nice, fresh medium, and gets great care, so it grows big and strong, sending its roots deep into the moist, airy medium. Those roots have “tailored” themselves on a cellular level to function optimally in that particular environment. Time marches on, and that potting medium starts to decompose, breaking down into smaller particles and becoming more and more compact, holding lots of water and starting to restrict air flow to the roots. Plus, minerals from your water and fertilizers, as well as plant waste products have been accumulating in the medium as well. The environment has definitely changed, but the roots have not and cannot.

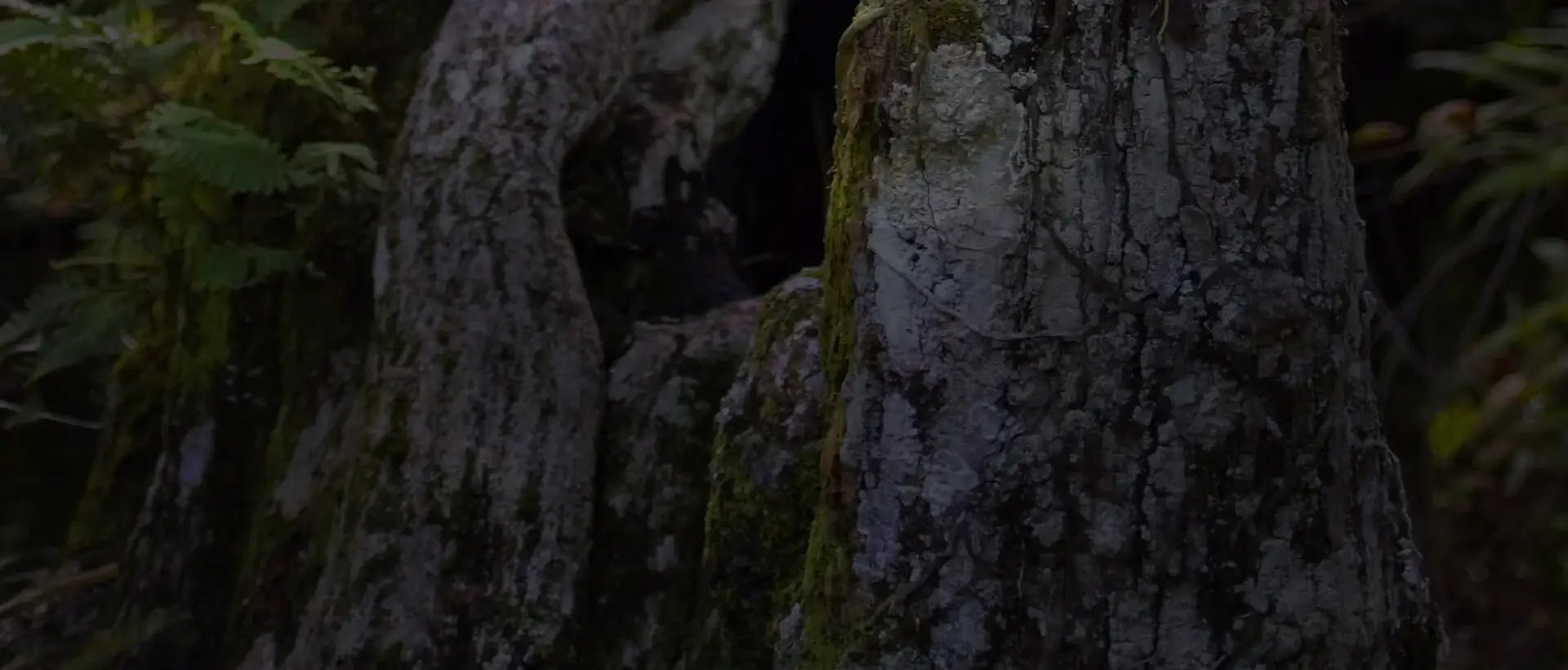

The black, vertical arrow in the image mark the nice depth to which the roots grew originally, but judging by their color and condition, they are failing in that changed environment. You will note, though, that there are new roots that look entirely different (see the yellow circle) that have grown from the ends of those old roots. Those nice, plump roots have grown with their cells optimized for that environment, even if it is an environment that is bad for the original root system.

One might speculate that the plant will therefore be okay, as it now has well-functioning roots, but unfortunately, while those newly grown root segments may be fine for that environment, the older root system is not, so will continue to deteriorate, ultimately completely separating those new roots from the plant, leading to its demise.

That is why, when considering repot- tingaplant,itisbesttodosojustasnew roots are emerging from the base of the plant, and not when the plant is dormant. Otherwise, root growth will resume only on existing roots. Those new, emergent roots will grow optimized for the environment and support the plant, while the old ones are expected to eventually fade away.

Keep in mind that the greater the difference between the “old” and “new” root zone conditions, the less optimal the old roots will be, so the more critical is the timing. One can avoid such setbacks by using good quality potting media components and repotting frequently, before the medium can significantly decompose and become compressed.

— Ray Barkalow is an engineer and scientist, and has been a hobby orchid grower for over 40 years. He has owned and operated First Rays Orchids since 1994, He can be reached at raybark@ firstrays.com.