Growing in full sun in its native habitat at the higher elevations of Brazil, Sophronitis coccinea flowers abundantly.

On the other hand, it is no less significant that most of those who import Brazilian Sophronitis species are presently the Japanese, despite their climate. One specialized Brazilian firm alone is exporting to Japan 1,000 plants of these species each month. Are these plants being purchased exclusively for use in hybridizing? The great quantities of plants being sold make this difficult to believe. In all likelihood, Japanese orchid growers are dedicating themselves to growing "mini" plants, and in this respect they are finding great satisfaction with Sophronitis species, and their deep red (ruby), unique flowers. It is apparent that they have been succeeding, with their extraordinary oriental patience, in growing these plants well— giving the appearance that Sophronitis culture is easy. As a matter of fact, my experience in collecting Sophronitis species in Brazilian forests, and in growing them over the past five years, has shown me that their culture really is not so easy. Furthermore, only 20% of the collected plants have flowers of good quality, while only 5% are really outstanding. Moreover, to obtain exuberant and high-quality flowering from these Sophronitis species, superior culture — or at least conditions similar to those where the plants were collected — is essential.

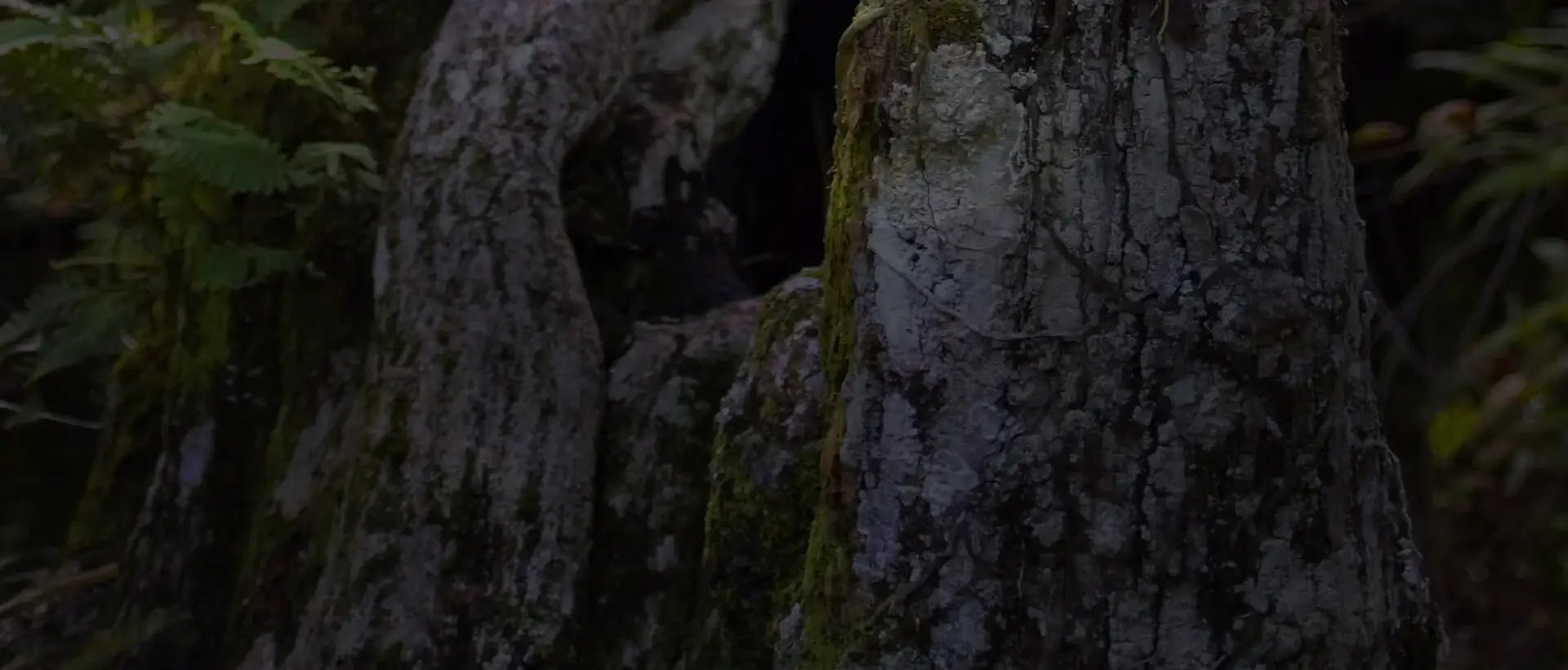

In heavy shade plants ofSophronitis coccineaare generally smaller and less floriferous. Note the dense carpeting of moss covering the tree on which the plants are growing.

I might point out that plants of Sophronitiss pecies found in nature do not always flower exceptionally; the ideal conditions necessary for this are found more often in cultivation. Despite the fact that plants of these species found in their native habitats are vigorous, their flowers are constantly attacked by wild bees, their pseudobulbs are often nests for the "Cattleya Fly," Eurytoma orchidearum, from which they lose their front bulbs, and they weaken due to the excessively hot temperatures which do occur in their environment. The luxuriant flowering of these species only takes place after the plants adapt themselves to ideal conditions of cultivation, and, very importantly, after they start receiving fertilizer. Plants grown in pots may do well without fertilizer, but they will not reach their potential come flowering time. By potential I mean that a plant in a small pot should easily produce six to eight flowers (see illustrations).

In nature, flowers o fSophronitis coccinea are often severely damaged by natural predators.

What follows, then, are general recommendations to make the cultivation of Brazilian Sophronitis species easier. Although I would like to discuss all aspects and factors which influence the culture o fSophronitis, it is important to mention that my own experiences are based upon observations of the habitats and culture of Sophronitis pygmaea, S. acuensis, S. coccinea, S. mantiqueira. S. brevipendunculata and S. cernua. As a matter of fact, all artificial cultures ofS ophronitis which I am familiar with in Brazil have one thing in common (the accompanying photographs clearly show this): the roots are plunged into a very humid medium which permits the formation of a green layer of moss on the surface. Thus, the culture of the Brazilian Sophronitis follows a certain number of rules which, if carefully observed, will result in good culture and flowering, whether in California, Florida, or even in New England.

NATURAL HABITAT

As I tried to demonstrate in my previous article on the subject (the ORCHID DIGEST for March/April 1983), in regions which I have explored there was considerable variation in clones of Sophronitis coccinea. In one certain area, leaf and pseudobulb form varied, in addition to the quality of the flowers. After careful exploration of the area as well as the plants, and prolonged discussions with Brazilian orchid growers in Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo, I came to a plausible explanation for this diversity of individuals. They are either natural hybrids of Sophronitis brevipedunculata with S. coccinea, orS. coccinea with S. acuensis. The last species, which is found at an altitude which ranges from 1,800 to 2,300 m, might have given rise to natural hybrids with Sophronitis coccinea, which is found at altitudes ranging from 1,000 to 2,000 m, since they both bloom at the same time. In the same way,Sophronitis brevipedunculata, found at lower altitudes (although close to the habitats of the previous species), might likewise be involved in some natural hybridization. The resulting hybrids never produce the same immaculate coloring of their parents; they tend to produce flowers of a sickly red.'

Sophronitiscernua generally appears in nature attached to humid rocks, on surfaces where sphagnum was previously formed under direct light, whereas Sophronitis brevipedunculata grows on tree trunks of small size, usually close to some source of humidity, but also under bright sun. Plants of these species may be cultivated in greenhouses with the same light intensity given cattleyas, perhaps even more; it doesn't make much difference. The decisive factor is neither adequate light intensity nor potting media with proper pH, but, as explained later, factors linked to low temperature and (a crucial point) high humidity.

LIGHT

In the forests which are their natural habitat, plants of Sophronitis coccinea, S. mantiqueira and S. acuensis are found growing vigorously under full sun, with their thickened foliage turning a characteristic darker color as a protection. In the same habitat, the same species can be found growing under shadowy conditions, with greener and less sappy leaves, but ever-flowering. Among them, various natural hybrids can be found along with, if one is lucky, the unique and very rare yellow variety.

It is mainly on top of the hills (where vegetation is sparse), and on top of trees fully exposed to light, that plants of Sophronitis better germinate and grow. Plants in bad shape taken from shadowy regions fully recover and produce much more vigorous growths when exposed to high light intensity in cultivation. Sophronitis can be grown successfully if the same light intensity given cattleyas is applied to them as well. Good growth is possible even under full sun, as long as the plant has been collected under the same natural conditions, or it has been gradually exposed to high light intensity and, as always, provided with high humidity and a medium which is constantly moist.

HUMIDITY AND TEMPERATURE

Besides requiring reasonable light intensity, Brazilian Sophronitis species grow well under relatively high humidity. The humidity found in their natural habitat comes from various sources, and it is, as it always occurs, related to temperature. Obviously, when both light intensity and temperature increase, it is the humidity of the air which helps to maintain optimum conditions. Sophronitis cernua, for example, has a greater tolerance of warmth than Sophronitis coccinea. The former blooms at sea level as long as there is reasonable air movement, while the latter does not, occurring only in habitats above 800 meters.

The trunk of a dead tree recently brought in from the wild supports a sizable colony of Sophronitis coccinea

Sophronitisacuensis andSophronitismantiqueira (the latter named after the Brazilian chain of mountains), however, occur at altitudes ranging from 1,800 to 2,300 meters. Cultivating these species in regions with altitudes around 1,000 m is possible, but the plants suffer from the environmental changes. They often wrinkle and decline under these conditions, flowering less and less each year. Moving plants of these species to even warmer regions (at lower altitudes) makes them "dwarfs" which soon die.

One year later, with ideal conditions provided in culture, this and other plants on the tree trunk pictured above have more than doubled in size and number of flowers produced.

Serra do Mar" and "Serra da Mantiqueira," where most of the Sophronitis species can be found, are very cold regions, at least to Brazilians! There, temperatures lower than 0°C (32°F) are registered during the winter; while during the summer the temperature does not exceed 30°C (86°F). Fortunately, these species are reasonably tolerant of variations in temperature, and they bloom satisfactorily if temperatures are no higher than 30°C (86°F), as long as the humidity {the decisive factor) ranges from 70-90%. In the forest habitat of these species, humidity is due to three main factors: 1, the mist that almost always occurs at dawn; 2, layers of sphagnum and humus on the host trees which, most important of all, provide constant evaporation all year long (see the habitat shots included with this article); and 3, the dense carpeting of big terrestrial bromeliads under the host trees which act as veritable reservoirs of water. This last factor is so vital to the survival of these species in the wild that its absence confirms their absence. I once explored an area for two or three hours without finding a single sophronitis. Only later did I realize that, though all the other environmental factors were adequate, the large terrestrial bromeliads were absent, and that this was the cause of my fruitless search. These bromeliads are responsible for a meaningful part of the humidity present in the tropical forests where Sophronitis species are found.

Humidity, then, is of extreme importance in Sophronitis culture. In the case of Sophronitis brevipedunculata in nature, the humidity comes from the swamps or bromeliads surrounding their host trees, whereas for Sophronitis cernua the constant humidity of the rocks and sphagnum ensures the same effect.

A bunch of grown-in clay pots filled with sphagnum moss, is a spectacular sight when the plants are in flower.

"Serra do Mar" and "Serra da Mantiqueira," where most of the species can be found, are very cold regions, at least to Brazilians! There, temperatures lower than 0°C (32°F) arc registered during the winter; while during the summer the temperature does not exceed 30°C (86°F). Fortunately, these species are reasonably tolerant of variations in temperature, and they bloom satisfactorily if temperatures are no higher than 30°C (86°F), as long as the humidity {the decisive factor) ranges from 70-90%. In the forest habitat of these species, humidity is due to three main factors: 1, the mist that almost always occurs at dawn; 2, layers of sphagnum and humus on the host trees which, most important of all, provide constant evaporation all year long (see the habitat shots included with this article); and 3, the dense carpeting of big terrestrial bromeliads under the host trees which act as veritable reservoirs of water. This last factor is so vital to the survival of these species in the wild that its absence confirms their absence. I once explored an area for two or three hours without finding a single sophronitis. Only later did I realize that, though all the other environmental factors were adequate, the large terrestrial bromeliads were absent, and that this was the cause of my fruitless search. These bromeliads are responsible for a meaningful part of the humidity present in the tropical forests where species are found.Humidity, then, is of extreme importance in culture. In the case of in nature, the humidity comes from the swamps or bromeliads surrounding their host trees, whereas for the constant humidity of the rocks and sphagnum ensures the same effect.

GROWING MEDIA AND WATERING

When well-grown,Sophronitis coccinea make impressive specimen plants.

Basically, any "fresh" mixture which has the ability to hold moisture may be used for sophronitis. Presently I am using sphagnum collected directly from the rocks — with better results than with any other medium. One year after being collected, plants of these species grown in sphagnum, whether in clay or plastic pots, develop deep, vigorous root systems; while those grown in osmunda, on the other hand, do not show such vigorous rooting (see illustrations). If sphagnum is used as the potting medium, clay as well as plastic pots are not as suitable. Even better results can be achieved if the pot to be used is made of osmunda or tree fern. This type of pot offers a cooler and thus healthier environment for the roots. If such containers are used, the type of medium provided is not terribly relevant. Please note in the accompanying illustrations that those plants which are growing best have a layer of live, green sphagnum growing on top of the medium — as is the case for the plants growing in situ.

Variation in form and color is so extreme in Sophronitis coccinea that no two cultivars look alike.

The use of "cinasita," a small-sized turface (a baked clay material) has not yielded satisfactory results inSophronitisculture, except when used as drainage material only. One way or another, though, whether it be tree-fern chunks, fir bark or assorted combination mixes, the fact is that sophronitis will do well as long as adequate humidity and moisture are present. When in doubt — contrary to accepted practice with cattleyas — always water!

Another alternative means of growing sophronitis is to establish the plants directly on live trees. The plants adapt perfectly when mounted on orange or lemon trees. Finally, sophronitis can be grown on pieces of wood. The accompanying pictures illustrate the good results possible with this method, in several cases obtained by Professor Osmar Judice. With abundant watering, he has produced intensely rooted plants which flower luxuriously.

FERTILIZING

In osmunda, root growth for Sophronitis coccinea is often quiet limited, and, consequently so is growth and flowering.

When Brazilian Sophronitis species are planted in sphagnum or directly mounted on lemon or orange trees, they don't seem to need large doses of fertilizer. The same applies when pots of tree fern are used — but not with any other medium. In this case, the plants should be fertilized weekly, or at least every fifteen days, during the fall and winter months when the plants are growing. During the summer it is advisable to reduce or stop fertilizing, starting up again by mid-autumn.

There is no doubt that my experiences with the culture of the Brazilian Sophronitis species are influenced by the fact that I grow these orchids in the same region where Sophronitis coccinea, S. mantiqueira. S. brevipedunculata and S. cernua are found. This allows me to deepen my knowledge of the growing habits and life cycle of these orchids, while, of course, making their culture easier. The artificial growing environments created for these Sophronitis species should be as similar as possible to the local conditions where the plants were collected. Though it is obvious that the tropics are particularly suited for the culture of these orchids, even in natural habitats there are variations in conditions, due to differences in altitude, humidity, and so on. There is no doubt that the Brazilian Sophronitis species can be grown and flowered well even in the Northern Hemisphere, as long as a few elementary guidelines are followed:

In sphagnum moss, on the other hand, root growth is luxuriant, pointing out how vigorous this and other Brazilian Sophronitis can be when provided with ideal growing conditions.

Basically, any "fresh" mixture which has the ability to hold moisture may be used for sophronitis. Presently I am using sphagnum collected directly from the rocks — with better results than with any other medium. One year after being collected, plants of these species grown in sphagnum, whether in clay or plastic pots, develop deep, vigorous root systems; while those grown in osmunda, on the other hand, do not show such vigorous rooting (see illustrations). If sphagnum is used as the potting medium, clay as well as plastic pots are not as suitable. Even better results can be achieved if the pot to be used is made of osmunda or tree fern. This type of pot offers a cooler and thus healthier environment for the roots. If such containers are used, the type of medium provided is not terribly relevant. Please note in the accompanying illustrations that those plants which are growing best have a layer of live, green sphagnum growing on top of the medium — as is the case for the plants growing in situ.The use of "," a small-sized turface (a baked clay material) has not yielded satisfactory results in culture, except when used as drainage material only. One way or another, though, whether it be tree-fern chunks, fir bark or assorted combination mixes, the fact is that sophronitis will do well as long as adequate humidity and moisture are present. When in doubt — contrary to accepted practice with cattleyas — always water!

A covering of moss over this tree fern pot containing sphagnum moss is an indication that the roots of this Sophronitis coccine are growing under ideal conditions.

Another alternative means of growing sophronitis is to establish the plants directly on live trees. The plants adapt perfectly when mounted on orange or lemon trees. Finally, sophronitis can be grown on pieces of wood. The accompanying pictures illustrate the good results possible with this method, in several cases obtained by Professor Osmar Judice. With abundant watering, he has produced intensely rooted plants which flower luxuriously.

When Brazilian species are planted in sphagnum or directly mounted on lemon or orange trees, they don't seem to need large doses of fertilizer. The same applies when pots of tree fern are used — but not with any other medium. In this case, the plants should be fertilized weekly, or at least every fifteen days, during the fall and winter months when the plants are growing. During the summer it is advisable to reduce or stop fertilizing, starting up again by mid-autumn.

Barren branches are suitable for Sophronitis species, however daily watering is necessary.

There is no doubt that my experiences with the culture of the Brazilian species are influenced by the fact that I grow these orchids in the same region where and are found. This allows me to deepen my knowledge of the growing habits and life cycle of these orchids, while, of course, making their culture easier. The artificial growing environments created for these species should be as similar as possible to the local conditions where the plants were collected. Though it is obvious that the tropics are particularly suited for the culture of these orchids, even in natural habitats there are variations in conditions, due to differences in altitude, humidity, and so on. There is no doubt that the Brazilian species can be grown and flowered well even in the Northern Hemisphere, as long as a few elementary guidelines are followed:

GENERAL RECOMMENDATIONS FOR CULTURE

Sophronitis rosea lacks the dark midrib found on the leaves of Sophronitis coccinea. Both species are equally well established on tree branches and trunks.

- Water the Brazilian sophronitis almost as much as you would miltonias or phalaenopsis. Select a medium which helps you to meet these moisture requirements.

- Provide high (80% maximum) humidity and keep the air in constant motion —otherwise, flowers will not appear. A buoyant, refreshing breeze is necessary for these species.

- Provide "cattleya" light conditions, or greater, as this is what these species often receive in nature. Sophronitis will grow well and bloom better in more-than-ideal light. Sometimes a bit more light will make a remarkable difference in the growth and flowering of the plants.

- Fertilize frequently, using Peters 18-18-18 water-soluble fertilizer at least every week when the plants are in growth, and every other week when they are not. Pot size is not critical with these species, but avoid using too small a pot. Repot the plants every two years in fresh sphagnum or other medium. Use any kind of pot you prefer. I prefer tree fern pots because they are easily obtained in Brazil, but clay or plastic pots are good as well.

- Remember, Sophronitis species prefer cool temperatures, not warm. Due to the altitude of their typical habitats, S. pygmaea and S. mantiqueira require the coolest temperatures, S. coccinea can tolerate slightly higher temperatures, while S. cernua can tolerate still higher temperatures.

- Try different microclimates in your growing area to your and your plants' advantage. "Warm and dry" will be near your heat source, "cool" will be found near your humidity source, while "full sun" will occur in the location nearest the glass or lights. Avoid warm and dry conditions with these species.

- Closely examine your plants; observe how they react to conditions and alter those conditions accordingly.

A rare yellow cultivar of Sophronitis coccineaThis cultivar 'Toyiama' grown by Kirk King received an 85pt CCM/AOS in 1996.

I have had great pleasure cultivating the Brazilian Sophronitis species; I am sure that you can enjoy them, too.

'In Brazil, sophronitis usually send forth new growth twice a year. But only those pseudobulbs formed during the winter (lower; those produced in the springtime do not. The only exception to this is Sophronitis mantiqueira which flowers during the summertime when no other Brazilian Sophronitiss pecies is in bloom

- The average rainfall for Teresopolis for the past 30 years varies from a high of 309.6 mm (12 inches) in December to a low of 36.4 mm (1.4 inches) in July. The average annual rainfall is 1,671.6 mm (66.8 inches). During the driest months, terrestrial bromeliads perform a meaningful role in providing sophronitis with humidity.

1 Orchid grower Sebastiao Nagase, of Sao Paulo, succeeded in crossing Sophronitis coccineaand S. brevipedunculata. The resulting hybrid presented forms similar to those of S. coccinea, but the "red" colors obtained were poorer and lighter than those of its parents.