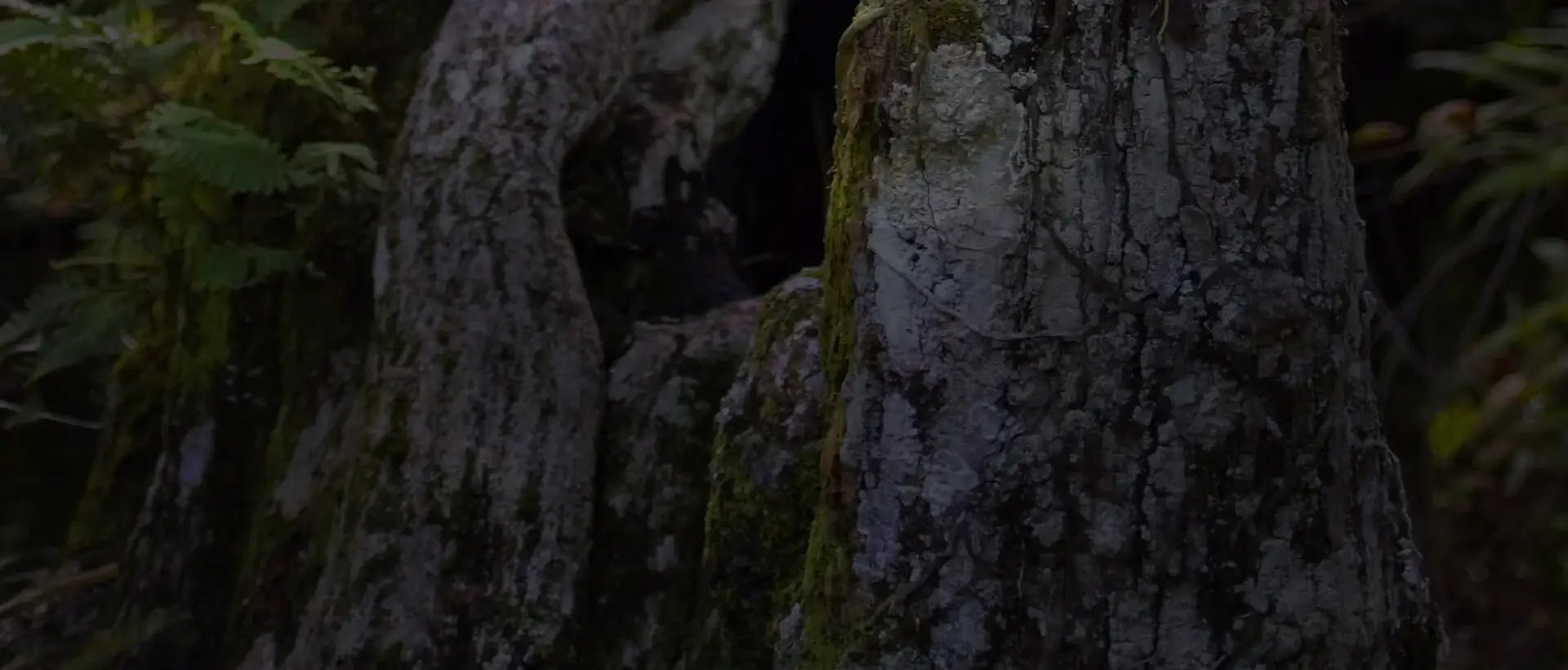

White Phalaenopsis Ringspots

Gallery

Symptoms

Light yellowish or whitish semi-circular or bull's eye-like spots on phalaenopsis leaves. Lesions can appear on either surface and may have a slightly sunken or rough appearance.

Treatment

No known treatment although the virus that causes this does not appear to move quickly through a plant so it may be possible to remove an affected leaf before lesions appear at the base of a leaf.

Prevention

Practice preventative hygiene with disposable gloves and sterilized cutting tools and control the presence of Thrips - insects known to spread this family of viruses.

Additional Information

Solving the Mystery/By Carlye Baker, PhD, David Davison and Carol Scoates

Samples from two different nurseries have tested positive for two tospovirus species. One sample tested positive for Tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV) and another tested positive for Impatiens necrotic spot virus (INSV).

One sample tested positive for Tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV) and another tested positive for Impatiens necrotic spot virus (INSV).

Further Reading

Adkins, S., T. Zitter and T. Momol. 2005. Tospovirus (Family Bunyaviridae, Genus Tospovirus), Fact Sheet PP-212. Plant Pathology Department, Florida Cooperative Extension Services, Institute of Food and Agriculture Sciences, University of Florida, Gainesville.

Hu, J.S., S. Ferrerira, M. Wang and M.Q. Xu. 1992. Detection of cymbidium mosaicvirus, odontoglossum ringspot virus, tomato spotted wilt virus, and potyviruses infecting orchids in Hawaii. Plant Disease 77:464–468.

Koike, S.T., and D.E. Mayhew. 2001. Impatiens necrotic spot virus found in Oncidium. Orchids — The Magazine of the American Orchid Society 70:746–747.

Pottorff, L.P., and S.E. Newman. 2006.Greenhouse Plant Viruses (TSWV/INSV).

(This article is reprinted courtesy of the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry, Plant Pathology Section.)

Carlye Baker, PhD, is a plant virologist in the Plant Pathology Section of the Division of Plant Industry working on orchids and other plant species. (e-mail bakerca@doacs.state.fl.us). David Davison is a plant pathologist in the Plant Pathology Section of the Division of Plant Industry working on fungal and viral plant pathogens. (e-maildavisod@doacs.state.fl.us). Carol Scoates is a laboratory technician IV, who assisted both Baker and Davison on this project. Plant Pathology Section, Florida Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services — Division of Plant Industry, Gainesville, Florida 32608.

PATHOGEN

Tospoviruses (Adkins et al., 2005) belong to the virus family Bunyaviridae, which are primarily animal-infecting viruses. The genus Tosporivus is the only plantinfecting member of the Bunyaviridae. Fifteen to 18 different species of tospoviruses have been recognized, including TSWV and INSV. TSWV has a large host range (800 plant species) and is mostly, but not exclusively, a viral disease found in field crops. INSV has a smaller host range and is mostly a virus found infecting ornamental greenhousegrown crops. Both viruses have been reported in orchids since the early 1990s (Hu et al., 1993; Koike and Mayhew, 2001).

VECTOR

Tospoviruses are transmitted from plant to plant by several species of thrips. The most common species that vectors these viruses is the western flower thrips (Frankliniella occidentalis).

DETECTION AND DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of these viruses in Phalaenopsis has proven difficult. These viruses do not appear to spread systemically in this host. Serological tests with nonsymptomatic leaves of infected plants are negative. The lesions, though spectacular on some plant leaves, appear to be local lesions and the titer (amount of virus in a given amount of tissue) of virus is low and decreases with time. This means that serological testing should be done soon after the appearance of symptoms. Historically, the symptoms have disappeared during the summer and then reappeared in the autumn to early winter when the plants were blooming.

CONTROL

The best control of a plant virus is always avoidance of infection. Obtain orchids from clean sources and grow orchids away from any host that could harbor these two viruses or their thrips vectors (Pottorff and Newman, 2006). This would include plants such as chrysanthemums, which are susceptible to both TSWV and INSV, and impatiens and prayer plants, which are susceptible to INSV. The control of weeds that could harbor either virus or the thrips vector is also warranted. Any plants with symptoms should be removed or at least separated from plants without symptoms.

Although early serological diagnosis is possible, this appears to be one situation where a viral diagnosis can be made with symptoms. White Phalaenopsis with the symptoms shown here apparently have been visited by thrips carrying one of two tospoviruses, TSWV or INSV.

FREE ACCESS: Orchid DealWire

Get notified when orchid vendors have special promotions and exclusive savings.