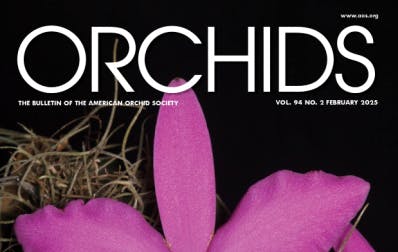

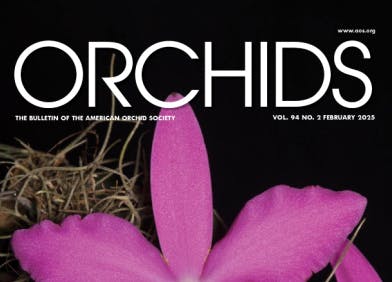

THE 2014 REDLAND International Orchid Festival in South Florida’s Homestead was one of the first orchid shows I ever attended. From a myriad of spectacular plants displayed in the exhibit and for sale in the booths, a batch of flowers with unusually intense magenta color at the H&R Nurseries from Hawaii stand caught my attention. They were the first-bloom seedlings of a splash-petaled semialba form of Cattleya violacea. The flowers were white with intense magenta marks on the sepals and petals with a hot magenta lip. The color combination, bold presentation and intoxicating fragrance were striking. I was hooked. Patti Lee, the founder of the Manhattan Orchid Society from New York and Eric Gottlieb from Miami, my orchid mentors, educated me on the flower quality, comparing the shapes and color patterns in the group, and helped me to select an outstanding plant. A native of Hawaii, Patti even negotiated “a Hawaiian” discount for me. Thank you, Eric and Patti! You will always be present in my collection through the many Cattleya violacea forms I have acquired over the years. My journey to learn about its history, geography and culture thus began.

[1] Cattleya violacea ‘Carlos magdiel’ hcc/AOS grown by carlos Granados. Photograph by Jorge Enrique Cespedes.

HISTORY

The species was first described by Carl Sigismund Kunth as Cymbidium violaceum in 1816. Kunth was a member of a fascinating expedition led by Alexander von Humboldt and Aime Bonpland to the equinoctial neotropics along the Orinoco River (von Humboldt and Bonpland, Vol II, 1814–1829). The records suggest that the plant sample was collected near the Torrents of Atures at Puerto Ayacucho in Venezuela. We should note that the genus Cattleya had yet to be established by John Lindley (1821–1824), and as with most orchids of the day, they were classified either as Epidendrum or Cymbidium (Aulisi and Foldats 1989).

The plant’s taxonomy changed several t imes. Based on samples collected by Robert Schomburgk in 1837 at the mouth of the Rupununi River in today’s Guyana, Lindley named the species Cattleya superba, ignoring Kunth’s findings (Lindley 1838). Heinrich Gustav Reichenbach transferred the name to the genus Epidendrum with two names: Epidendrum violaceum (Reichenbach 1861) and Epidendrum superbum (Reichenbach 1874). Based on Kunth’s naming, the current binomial Cattleya violacea was proposed by Robert Allen Rolfe 73 years later in 1890 with other names as synonyms (Rolfe 1890). Cattleya violacea var. superba and Cattleya superba are still in use in South America today.

Commonly, C. violacea is known as “Cattleya superba of the Orinoco.” The name C. violacea refers to the violet color of the typical clones (Aulisi and Foldats 1989).

HABITAT

Cattleya violacea is a bifoliate species from the equatorial neotropics. With the largest distribution of any Cattleya species (ca. 1.54 million square miles [4 million square kilometers]), its extended territory spans over the Orinoco and Amazon River basins through Guyana, Venezuela, Colombia, Brazil, Peru, Ecuador and Bolivia (Aulisi and Foldats 1989, Withner 1988, Romero 1997). It is fascinating to know that such a large area can share very similar growing conditions (Baker and Baker 1990). The plant grows in very hot and humid tropical environments at elevations from sea level to about 1,475 feet (0–450 m) frequently on trees close to rivers, lakes and creeks. Alek Zaslawski (pers. obs.) from AWZ Orchids reports that plants were found at an elevation of about 1,475 feet (450 m) in the higher areas of the Surumu River, which runs in Roraima State in Brazil, south of Pacaraima. At the riverbanks, the plants are exposed to extra humidity from the water, excellent air circulation, bright light and extra light reflections from the river surfaces. Close to the water’s edge, the vegetation clears, which provides extra light and aeration compared to the dense tree canopies inside the forest.

[2] Cattleya violacea ‘Doña Ana’ am/AOS grown by Eric Arce.

In the Venezuelan State of Apure, extreme conditions are defined by wet and long dry seasons, and the plants live on short trees low to the ground (around 1.9 feet [50 cm]). Semialba and caerulean forms were reported to be found in this region (Aulisi and Foldats 1989).

It is said that in some parts of Brazil near the Rio Negro, the plants occasionally get submerged in the water during the rainy season, which causes the river to rise tens of feet (meters) above their natural beds. The Amazon River rises during the rainy “winter” season (mid November through May) in the central Amazon that surrounds the city of Manaus, reaching its peak usually in May or June. This timing coincides with the blooming season of C. violacea in the area. During some extremely wet years, the Amazon River level can rise up to 50 feet (15 m) between lowest and highest points, thus engulfing the vegetation (Schultz and Parsons 2024). Fascinating! The water falls during the drier “summer” season (June/August until October). Although the water level is lower, the humidity always remains high due to the evaporation from the surrounding forest.

[3] Cattleya superba pictured in Lindley’s Sertum Orchidaceum, 1838.

One could spend a lifetime exploring the vastness of the Amazon region, discovering centers of C. violacea habitat. Zaslawski writes about visiting a huge archipelago called Anavilhanas located in the Rio Negro near Manaus. This is a labyrinth of around 400 islands most of which are underwater during the high water season (flooded forests are locally called Igapó) and only can be accessed by boat. In this area, the Rio Negro is almost 12.4 miles (20 km) wide, and C. violacea is quite present.

The region around Manaus, State of Amazonas in Brazil (not far from the Equator), has been identified as one of the largest C. violacea habitats (Baker and Baker 1990). The city is located at the very center of the Amazon basin, where the Solimoes and Rio Negro merge to form the Amazon River. Zaslawski details that, although the Amazon area is vast and the rainy–dry seasons can vary from region to region, climate conditions around Manaus are still frequently used for reference.

[4] Known centers of Cattleya violacea habitat in South america. courtesy of the Global Biodiversity Information Facility.

The weather conditions are consistently warm all year, with daytime readings near 85 F (29.4 C), cooling to near 70F (21.1C) at night. Diurnal range averages 12–16F (7–9C) throughout the year, and the humidity remains in the 70–80 percent range. Heavy rains persist through the year, except somewhat drier conditions in January, February, and March (Baker and Baker 1990).

Another center of C. violacea distribution spans across Rondônia and Mato Grosso States. From his visits to Rondônia State, Zaslawski notes seeing C. violacea thriving in areas of vegetation known locally as cerrado, such as that close to the town of Presidente Médici. Although sparsely forested and with poor quality sandy soil, the climate is not dry. The ground is frequently soaked with water. The vegetation includes shorter spaced-out trees providing good light and aeration to its epiphytes. Even with the rivers and lakes absent, C. violacea populations flourish in these moist conditions. Notice that the cerrado forest in Rondônia is completely different from the typical much drier cerrado biome vegetation of the large area southeast of the Amazon basin.

[5] Cattleya violacea (Semi-Alba Flamea) ‘Crownfox’ FCC/AOS.

Mato Grosso tends to the more typical drier cerrado forest biome, a semihumid tropical savanna rich in endemic fauna and flora. Although all the species color varieties are well described from the Amazonian region, color variety data from the cerrado forest is missing.

BLOOMING SEASON

In different parts of Brazil, the blooming season ranges from December to the middle of June. At their greenhouses in Espírito Santo State, the main blooming season at AWZ Orchids occurs from September to October. In equatorial Venezuela, where the seasons are less defined, it is said to flower all year round, particularly from January to September, with more scarce flowering in October to December (Baker and Baker 1990). Blooming typically occurs from April to June in the Northern Hemisphere. With good culture, the plants can rebloom in July or August, although the spring blooming is typically much stronger. Harry Akagi from H&R Nurseries in Hawaii reports that their C. violacea bloom three times a year with bigger and more vibrant flowers in cooler months (Akagi pers. obs.).

[6] Cattleya violacea (Coerulea) ‘Carola’ AM/AOS.

[7] City of Manaus during the dry season.

[8] City of Manaus during the wet season.

CULTURE

Cattleya violacea has an unjust reputation of being difficult to grow. As the following sections detail, there are several pointers derived from the observation of the natural environment that can be applied to swiftly improve its thriving. The reader should always be aware, however, of their own growing conditions and ways to adjust them to fit the plant’s cultural requirements.

TO WATER OR NOT TO WATER

The environmental data does not suggest that any rest period is needed for C. violacea. Withner observes that due to their consistently hot and humid growing conditions in nature, the plants should be watered continuously, without any rest (Withner 1988). Baker and Baker note that according to Oregon State University Extension Service, every plant needs a rest period, however brief. In this case, it would happen during the drier winter months (Baker and Baker 1990). AWZ grow their C. violacea successfully in their greenhouses near the municipality of Viana which is ca. 984 ft (300 m) above sea level. Although warm and bright during the day, the nights are cooler. The plants still thrive. Zaslawski also reports slowing down a bit with watering and fertilizing during their winter months. Unfavorable conditions that can lead to plants’ demise can be triggered by a combination of rain and cooler temperatures.

[9] Cattleya violacea habitat at Anavilhanas, close to Manaus during the wet season.

[10] The same habitat during the dry season.

With multiple AOS awards, including two First Class Certificates (FCC) from the AOS, Ben Oliveros of Orchid Eros proves that C. violacea can be grown in cooler conditions too. The testimony to his growing mastery is the fact that Orchid Eros Nursery is located 1,700 ft (ca. 533 m) above sea level on the slopes of Kilauea Volcano on the Big Island of Hawaii. The temperatures are suitable for intermediate growers (65–80 F [18–27 C] in the summer and 55–75 F [13–24 C] in the winter) rather than warm-growing species. With seasonal rains in the winter, Oliveros agrees with Zaslawski that the core of his C. violacea culture is to keep the plants dry in the winter. This is key when the temperatures become cooler.

Remember my first C. violacea from Redlands 2014? Well, it did not make it, and many others did not either. Or in other words, they made it to Orchid Heaven!

I could not figure out what I was doing wrong, giving them the same care as I did for other Cattleya species in my hot South Florida outdoor shade house. It was not until 2017 that I sent some pictures of my unhealthy plants to Harry Akagi at H&R Nurseries, pleading for help. His advice was simple: use open plastic baskets with well drained medium or mount them and mostly water a lot. The phrase that registered even more vividly in my mind was “Treat them like vandas!” Besides Cattleya species, Vanda species are another passion of mine, and at that time, I had already figured out Vanda culture to a greater degree and was having good success.

What an AHA! moment! I promptly followed Harry’s instructions for the plants that were beginning to root and began watering. I already knew not to touch the bifoliates, or any Catts for that matter, when not in the initial root explosion stage. I kept watering them every time I would water vandas two or three times a week, in the dry spring days even more frequently. From Thanksgiving to Valentine’s Day, I would reduce to two waterings per week. For South Florida, this made sense, and the results were unbelievable. Plants that looked weak and desiccated came alive, sprouting lush roots and commanding new growths. Thank you, Harry!

[11] Station # 82331, Manaus, Brazil, Lat. 3.1°S, Long. 60.0°W, at 144 ft. (44 m). Temperatures are calculated for an elevation of 1,300 ft. (396 m), resulting in probable extremes of 97.1 f (36.2 c) and 59.1 f (15.1 c). Average maximum and minimum monthly temperature, diurnal range, rain, humidity and number of clear days create a fine picture of the environmental conditions. Read values for the northern hemisphere top to bottom and for the south hemisphere (natural habitat) bottom to top. Reprinted from Baker and Baker 1990.

MEDIA

In their habitat near the city of Manaus, the favorite tree of C. violacea is called Araparí. In Rondônia, they can be spotted particularly on the White Charcoal tree known as Carvão Branco. Know your conditions. I have seen C. violacea successfully grown in plastic pots with coarse bark (H&R Nursery, Orchid Eros) and coarse bark mix (Krull-Smith). Withner and Baker and Baker also suggest growing them on slabs or in baskets with excellent drainage. This is similar for Cattleya wallisii (eldorado) that overlaps in territory with C. violacea. Fast draining medium is the key here. AWZ grow their plants mounted and in baskets in their nursery in Viana where it is quite humid. Mounting ensures a healthy root system and disease prevention.

For me, free draining clay pots or plastic baskets completely empty or filled with some ceramic pellets did the trick. Even better, these plants seem to enjoy mounting on cork or cypress planks. For coastal South Florida, everything disintegrates quickly due to the humidity, rain, and salinity in the air. Mangrove root slabs, if I can find them, seem to be most durable.

As with other bifoliate cattleyas, it is important to know when to repot and divide. The best time is when the plant is just about to break into new root growth. Take care not to disturb these new roots, spray them with a fungicide, and place the plant into a shadier area until the roots completely attach. It is recommended that a division for this species consists of at least f ive healthy pseudobulbs.

LIGHT

As noted above, the plants are exposed to bright light (like other Cattleya species) and even full sun with extra reflected light from water surfaces throughout the year in their natural environment. Interestingly, the light intensity seems to dictate their size: more light brings shorter growths, and less light results in the plants growing taller (Cassano pers. obs.). Cesar Wenzel also reports on various growing habits, visiting habitats from Mato Grosso state to Venezuela, where an almost 4-foot-tall (1.2 m) plant with 12 flowers was collected (Wenzel pers. obs.).

In 2022, the neighbor’s house just to the east of my property sold, and as part of the new owner’s quest for the property’s redesign, they cut down the thick patch of palms hanging over my shade house, blocking the sun’s morning rays. While devastating (yes, they cut some palms that harbored active ecosystems for birds and squirrels), removing the lush foliage resulted in new, brighter light conditions for orchids. Suddenly, the daylight hours extended greatly.

But of course! I remembered that C. violacea plants live high on the trees, often exposed to full sun with extra light from reflections of the rising and receding river.

Not only did I not have enough light intensity previously, I also did not have enough hours of light! My light days were too short, I realized.

Vandaceous species began blooming two to three times a year. My C. violacea plants began offering two blooming seasons: an expected strong one in April–May and a somewhat weaker but still delightful second season later in the summer (July–September).

WATER QUALITY

It goes without saying that rainwater in nature is considered pure, meaning its pH is slightly acidic, ranging between 5 and 6, with total dissolved solids (TDS) near 0 parts per million (ppm). In one of our conversations, Roy Tokunaga from H&R Nurseries stressed to keep the total mineral ion buildup to a minimum. Indulge me for a moment in my water purification journey that helped my C. violacea (and in fact, all orchid) culture.

I became curious about the quality of our city water and sent two 1.1 oz (33 ml) bottles of it to University of Florida Analytical Services Laboratories for testing in 2019. The results arrived within a couple of weeks. Although the water was only moderately hard and the electrical conductivity measurements (indicating TDS) were within the limit, its pH was surprisingly high at 8.5. Water quality may fluctuate over time, and thus I acquired a portable TDS and pH meter to monitor it periodically. After trying a few devices, I settled on the AI104G GroStar Series GS4 pen tester from Apera. I was further surprised to find out that the calibrated TDS measurement fluctuated to over 230 ppm and pH sometimes reached 9.5!

To put these measurements in perspective, it is recommended that TDS should be no more than175 ppm after the addition of fertilizer, and pH should remain slightly acidic at around 6.5 (Bottom 2019). Some growers, however, argue that higher ppm and lower pH (down to 5.5) is acceptable when the plants get periodically flushed with pure water.

The reason for lowered pH is to maximize the absorption of nutrients. This told me that adding fertilizer to such hard water would increase the TDS to the level of burning roots and damaging the plants. Additionally, some of the important nutrients, such as nitrogen and phosphorus, and micronutrients, such as calcium, iron, manganese, boron, copper and zinc, would not get properly absorbed at such high pH (even if a bit lower with the addition of the fertilizer).Recommended periodic flushing with water without additives to dissolve any salt buildup did not work either, as my water had a lot of salts to begin with. I also learned that extra chlorine and chloramine are added to our city water. Action had to be taken.

The AOS accredited judge Judy Bailey from our West Palm Beach judging center suggested purchasing a shower filter to begin with. How clever! These mechanical filters remove chlorine and chloramine and are inexpensive. Thank you, Judy! Once again, a consultation with Roy Tokunaga was needed. Roy suggested that I investigate Hydro Logic Reverse Osmosis (RO) systems to further purify my water. Although the system itself was not inexpensive, and I also expected higher water bills due to 1–1.5 gallons (3.785–5.678 l) of wastewater for every gallon (3.785 l) of purified water, I decided to go for it in the spring of 2022. The RO unit helped to eliminate any salts; however, pH still needed to be corrected. I tried citric acid, phosphoric acid (as suggested by Dr. Motes, 2008), 3% vinegar, and 30% vinegar to lower my pH. The most practical and cost effective for me proved to be 30% vinegar from the local hardware store. Adding 1–2 teaspoons (5–10 ml) of such strong vinegar to a 50-gallon (189 l) barrel of RO water was effective in reaching the desirable pH level. With the help of a 1.5 horsepower pump and a non-kinking stainless steel water hose, I was able to get the water into action! The results were immediate and remarkable. After a couple of waterings, the plants reacted with a refreshed growth activity.

Oh, how I wish I could have a well. However, our city does not allow well drilling because of the ocean’s proximity. I should thus note that I tend to alternate between RO water and ½ RO and ½ tap water due to the high expense.

One other watering correction improved my C. violacea culture tremendously. During one of his visits, my friend Dr. Leslie Ee suggested that I consider installing an automated watering system. In 2023, I indeed installed a simple time-controlled misting system for both vandas and C. violacea for daily watering. On hot summer days, they receive 15 minutes of water twice a day: early in the morning and late in the afternoon. With C. violacea, I observed that misting created that extra humid environment like their natural growing conditions, and they thrived even more!

FERTILIZER

As with all cattleyas, a weekly weak dose of balanced fertilizer during the growing season is generally recommended. AWZ fertilizes with an 18– 18–18 formulation even more frequently: two or three times per week, totaling about 180 ppm of nitrogen. During their winter, they reduce fertilizing to half, skipping days when unfavorable weather conditions (rain and cooler temperatures) prevail.

When I began growing orchids, Dr. Martin Motes’ book Florida Orchid Growing: Month by Month (2008) became my primary go-to reference. It took me a couple of years to realize that the South Florida conditions in Homestead that he describes were slightly different from the South Florida conditions of my coastal backyard. Firstly, I live very close to the ocean, which means higher temperatures throughout the year, less rain (our city lies in a rain shadow area) and perhaps even more salt in the air.

[12–13] Cattleya violacea habitat in the cerrado forest in Rôndonia state, Brazil.

My fertilizing program followed the book, which suggests application of balanced fertilizer (such as Peters 20–20–20) and low phosphorus fertilizers. Once, I visited my friend and grower par excellence Valerie Leonard. I saw her and her client’s collections of blooming orchids and was blown away by the lushness of the blooms. Her secret, she claimed, was the extensive use of bloom booster. I set out to try it. In my weakly weekly feeding program, I replaced the balanced and low phosphorus fertilizers with 12–48–8 from Southern Ag. The results were remarkable. Vandas responded within a couple of weeks with a burst of blooms, and the cattleyas followed. My Vanda tessellata and Vanda denisoniana plants now bloom three to four times a year, and I suspect that the extra summer bloom of C. violacea has much to do with the bloom booster applications. I supplement it with kelp and micronutrients.

[14] Blooming seasons in the habitat. Courtesy of Alek Zaslawski.

I tend to withhold fertilizer from C. violacea in the drier months. The period between Thanksgiving through Valentine’s Day is a good rule of thumb. This is where their culture differs from vandas that get fertilized throughout the year. However, no gloves fit all. The point is to be inquisitive about your own growing conditions, particularly if these are outdoors. Solutions are awaiting. Natural cues and friends are there to help.

[15] Cattleya violacea var. alba ‘Odom’s Orchids’ AM-CHM/AOS.

CONCLUSION

Cattleya violacea is an Amazonian bifoliate beauty worth having in any collection. Its striking presentation, long lasting flowers, strong fragrance and straightforward culture predestines it to become one of the IT plants in the years to come. Just read the follow-up articles on the extensive line breeding already done in its semi alba flamea and other color forms.

Although the natural habitat of C. violacea is extremely large, the plants have often become the victims of poaching. Due to their bright flower coloration, they can be spotted easily from the boats parading the rivers, and massive deforestation has also contributed to their rapid disappearance. With extensive line-breeding programs in several nurseries, seed-raised plants have become widely available. Their form and color varieties exceed those of collected specimens. Look for C. violacea at your next orchid show visit!

Acknowledgments

This article would not have been possible without the extensive consultations and help of Alek Zaslawski from AWZ Orchids. Many thanks to my readers Alek Zaslawski, Ron Kaufmann and Leslie Ee for further invaluable insights.

References

Aulisi, C. and E. Foldats. 1989. Monograph of Venezu elan Cattleyas and Its Varieties. Caracas, Venezuela: Editorial Torino.

Baker, C. and Baker, M. 1990. The Warm-Growing Cattleyas of the Northern South America. American Orchid Society Bulletin, 59(9):904–908.

Bicalho, H.D. and J. Miura (eds). 1983. Native Orchids of Brazil. Associacao Orquidofila de Sao Paulo. 2nd edition.

Bottom, S. 2019. Soluble Salts. St. Augustine Orchid Society. Retrieved on 10/12/2019 from https://staugorchidsociety.org/PDF/SolubleSaltsbySueBottom.pdf x Cassano, A. 2024. personal observation.

Global Biodiversity Information Facility. Cattleya violacea distribution map retrieved gbif.org on October 10, 2024.

Lindley, J. 1975. Sertum Orchidaceum. A Wreath of the Most Beautiful Orchidaceous Flowers. London: James Ridgway and Sons, 1838. New York, Amsterdam; Johnson Reprint Corporation, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. 1975.

Motes, M. 2008. Florida Orchid Growing: Month by Month. Redland Press, Redland, Florida.

Oliveros, B. (Orchid Eros Nursery). 2024. personal observation.

Reichenbach, H.G. Epidendrum violaceum. In Walpers, W.G. Annales Botanices Systematicae. Lipsiae, Sumtibus F. Hofmeister.

Reichenbach, H.G. 1874. Xenia Orchidacea - Beiträge zur Kenntniss der Orchideen. Vol II, Leipzig: F. A. Brockhaus.

Rolfe, R.A. 1890. New or Noteworthy plants. The Gardeners’ Chronicle : A Weekly Illustrated Journal of Horticulture and Allied Subjects. Vol. 8, p. 620. Retrieved 9/20/24 from https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/25925216.

Romero, G.A. 1997. Venezuela paraíso de ORQUIDEAS. Armitano Editores.

Schultz, A.R. and J.J. Parsons. Amazon Rive Animal Life. Retrieved 10/10/24 from https://www.britannica.com/place/Amazon-River/Animal-life

Tokunaga, R. (H&R Nurseries). 2022. personal observation.

von Humboldt, A. and A. Bonpland. 1814–1829. Personal narrative of travels to the equinoctial regions of the New Continent during the years 1799–1804. London: Printed by Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, Paternoster Row; J. Murray, Albermarle Street ; H. Colburn, Conduit Street. Reprinted Benediction Classics, 2012.

Wenzel, C. (Wenzel Orchids). 2024. personal observation.

Withner, C. The Cattleyas and Their Relatives, Vol. I: The Cattleyas. Timber Press.1988.

Zaslawski, A. (AWZ Orchids). 2024. personal observation.

— Dr. Juraj Kojš is an Associate Professor at the University of Miami’s Frost School of Music, where he combines his passion for music and orchids in innovative ways. He is the creator of the Orchid DNA Music project and the founder of the Foundation for Emerging Technologies and Arts, Inc. (FETA), which promotes experimental and interdisciplinary art forms. Dr. Kojš’s works have been commissioned by prestigious organizations such as The Knight Foundation, The Quiet Music Ensemble, Miami Light Project, Meet the Composer, Harvestworks, Miami Theater Center, Miami Live Arts, Deering Estate, and Vizcaya Museum & Gardens. In addition to his musical achievements, Dr. Kojš is an accredited American Orchid Society judge. He is the past president of the Coalition for Orchid Species and a board member of the Miami Beach Orchid Society. He also chairs the annual Orchids & Arts Festival at the Miami Beach Botanical Garden. He has received over 60 awards from the AOS to date. His multifaceted career reflects a unique blend of scientific rigor, artistic creativity, and a deep love for orchids (email j.kojs@miami.edu).